Article

February 28, 2022

Achieving equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines requires a better understanding of who is getting vaccinated

The rapid spread of the Omicron variant around the world has been one of many consequences of global vaccine inequity. New mutations and variants of the Coronavirus will continue to emerge and the unvaccinated elderly, people with comorbidities or health workers will continue to face an increased risk of hospitalisation or even death if infected. Yet data on who has been able to access vaccines within low- and middle-income countries is almost non-existent, making it difficult for national governments, their partners and the global community to identify gaps and provide targeted support.

While high-income countries have vaccinated the majority of their populations – some are well into the rollout of booster shots for all adults – low-income countries have vaccinated on average just 11.18 % of their populations with at least one dose. These numbers hide even worse disparities between countries – the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, has vaccinated less than 1% of its population with at least one dose.

The logistics of distributing these vaccines is complex and costly. They need to be kept at low, or sub-zero temperatures, in often hot and humid climates. Combined with other challenges like lack of road infrastructure or even on-going conflict, it becomes clear why many rural and under-resourced areas aren’t receiving the doses donated by COVAX, the global vaccine initiative. In South Africa, for example, mobile vaccination trucks have been used to try and increase vaccination rates in rural areas, as travel costs have been identified as the key reason for over-60s not accessing vaccines in the numbers expected. In Uganda and Malawi, boats and fast-track teams made up of vaccinators, health promoters, dramatists and a public address system are used to deliver vaccines to island communities and to increase uptake.

Supply issues have made planning and distribution difficult in many countries, and there has been criticism of lack of transparency in the order process, and of vaccines, once delivered, having short shelf lives. A joint statement from the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, the Africa Union, and the African Vaccine Acquisition Trust pointed out that the majority of dose donations to-date had been ad hoc, provided with little notice, and had imminent expiry dates. This has made it extremely difficult for countries to plan vaccination campaigns and increase demand particularly in rural and hard to reach areas. Indeed, many countries have been pressured to use soon-to-expire doses quickly in order to demonstrate their need to donors to guarantee a continued supply – factors that ultimately led many governments to open up vaccination to non-priority groups and the general public.

The question is: how can we ensure everyone living in a low or middle-income country who wants the vaccine gets it?

Equitable vaccination for priority groups

While Omicron has galvanized attention around the need for vaccine equity between countries, the need for equitable access within countries has not been making headlines. There appears to be a sense among global stakeholders and donors that as long as vaccines are delivered, the responsibility within the receiving country falls to the national government and partners on the ground despite the many hurdles they face.

To date in 2022, it seems the supply of vaccines to low and middle-income countries has increased, but many are still not carrying out priority vaccination for high risk groups. Short notice donations continue to present challenges when it comes to targeted national or regional vaccine campaigns.

More data and transparency needed to target priority groups

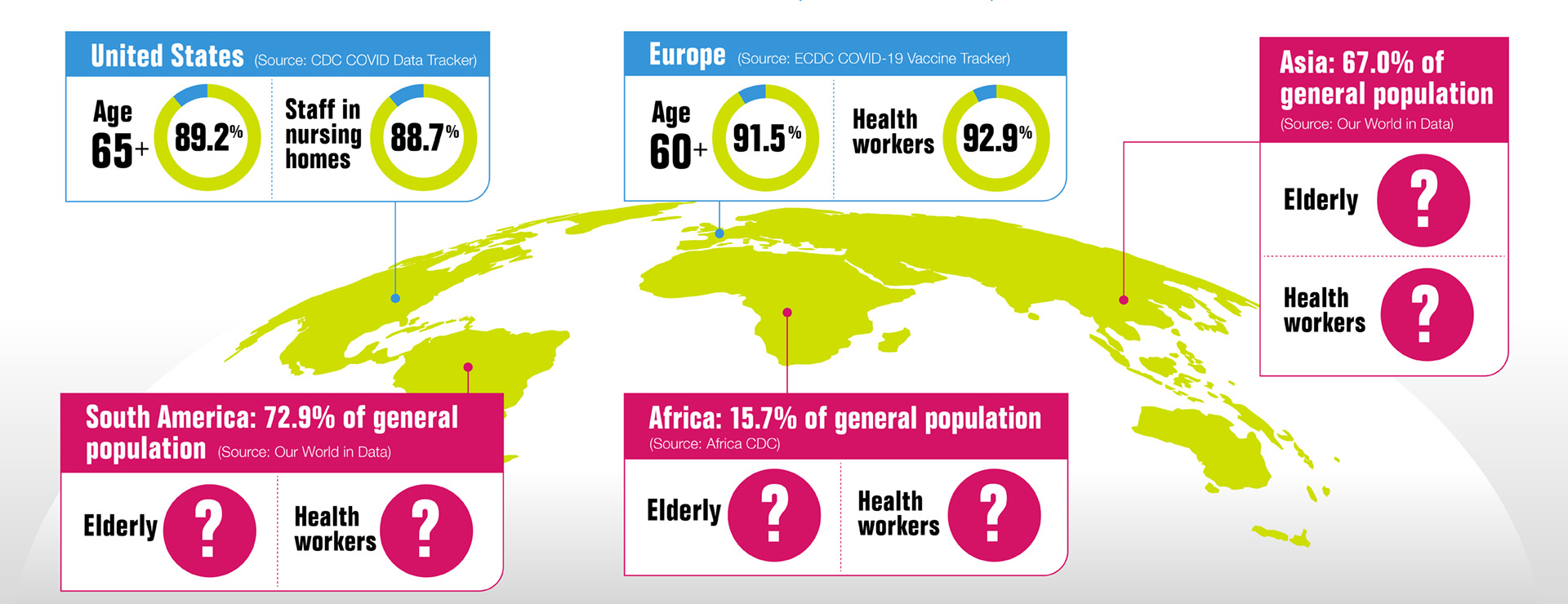

A lack of data on vaccination rates among priority groups doesn’t help, leading to a limited understanding of vaccine accessibility within countries. But what little information is available is concerning.

Uganda is one of the few countries which has made some vaccine data public. According to its Ministry of Health, only 15.6% of those in vaccine priority groups had received a second dose by 5 November 2021. These included health workers, teachers, security personnel, those aged 50 years and above and those below 50 years with co-morbidities.

A few months earlier, the Ministry published data on the vaccination rates of those individual priority groups. At that time, only 35.5% of health workers and 8.8% of those above 50 years had been fully vaccinated. Compare this to 83% of health workers and 82.3% of the elderly in EU/EEA countries who were fully vaccinated.

By collecting and publishing data about vaccination rates of priority groups, governments and their partners can more effectively target, draw attention to and support vaccination efforts aimed at the most vulnerable.

Transparency is key to building the knowledge and trust needed to achieve adequate support for equal access to vaccines, within and between countries, in addition to countering misinformation which feeds into vaccine hesitancy – a concern highlighted by 132 United Nations member states.

It will also require global and national efforts. To ensure no one is left behind, all governments whether they are procuring, donating, or receiving vaccines need to communicate clearly and consistently with their citizens, establish safe channels for reporting concerns, and encourage monitoring of the vaccine rollout by independent parties such as civil society organisations.

The WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said at the end of December, “Countries can’t boost themselves out of the pandemic.” The world’s best tool against continued infections and new variants is global vaccine equity, but it can’t be achieved without increased transparency. More data and information about vaccination progress is needed urgently to ensure everyone has access – who is getting vaccinated and where? And who is not?

Through improved transparency, the world can collectively ensure that getting vaccinated in 2022 is not determined by location, education, personal contacts, or wealth, but by need. No one is safe, until everyone is safe.